ISLAND ANALYSIS

Analyses of Sable Island’s vegetation, historic position, current topography and climate data help determine where the landscape is most stable. Understanding why and how landscape changes occur make it possible to select optimal locations for development.

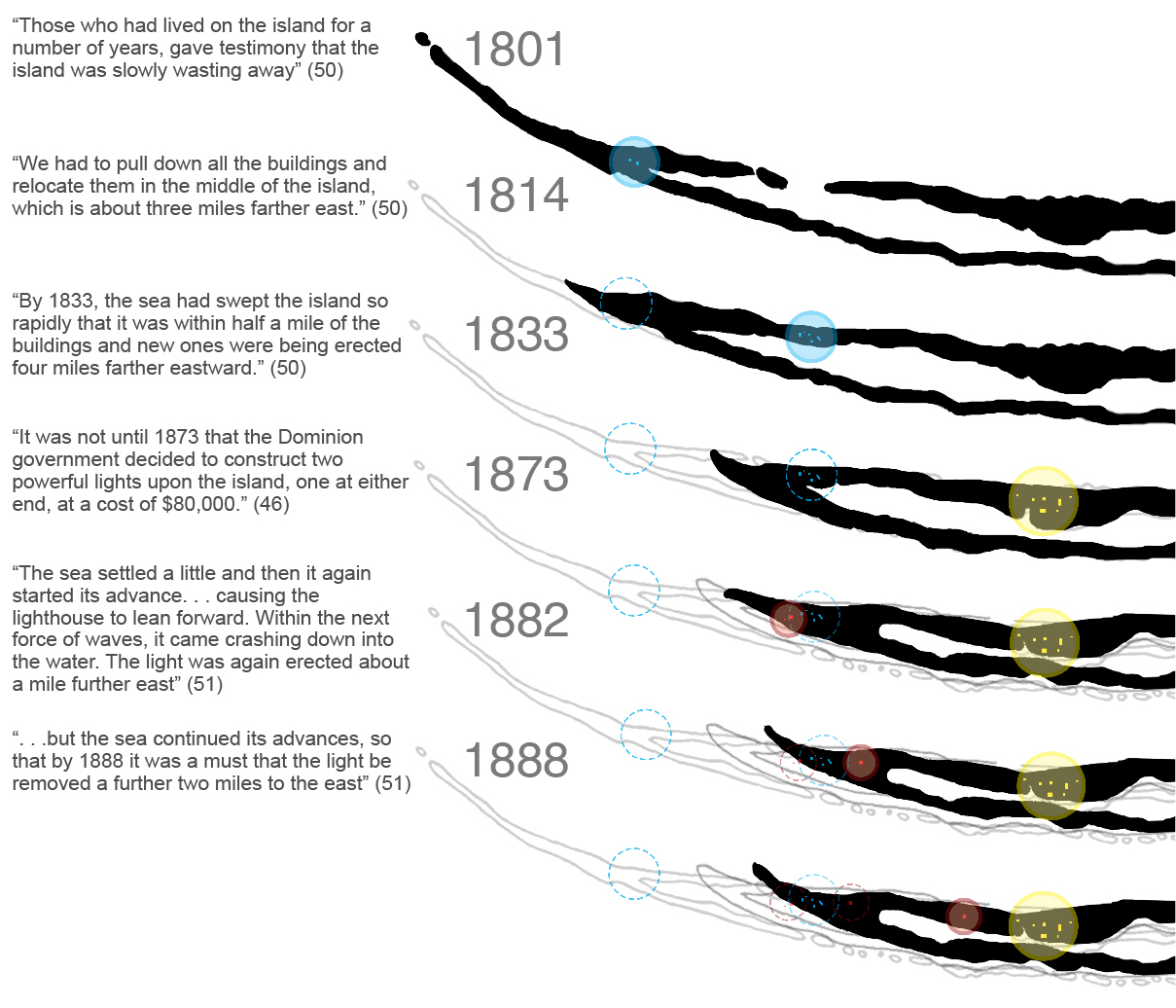

The above diagrams are graphic interpretations of Jack Zinck’s description of building relocations and reconstructions due to changing shorelines on Sable Island. (Shifting Sands 1979, 46-51). Shorelines are estimated using Zinck’s descriptions, and historic maps shown in Campbell’s Sable Island Shipwrecks: Disaster and Survival at the North Atlantic Graveyard (1994).

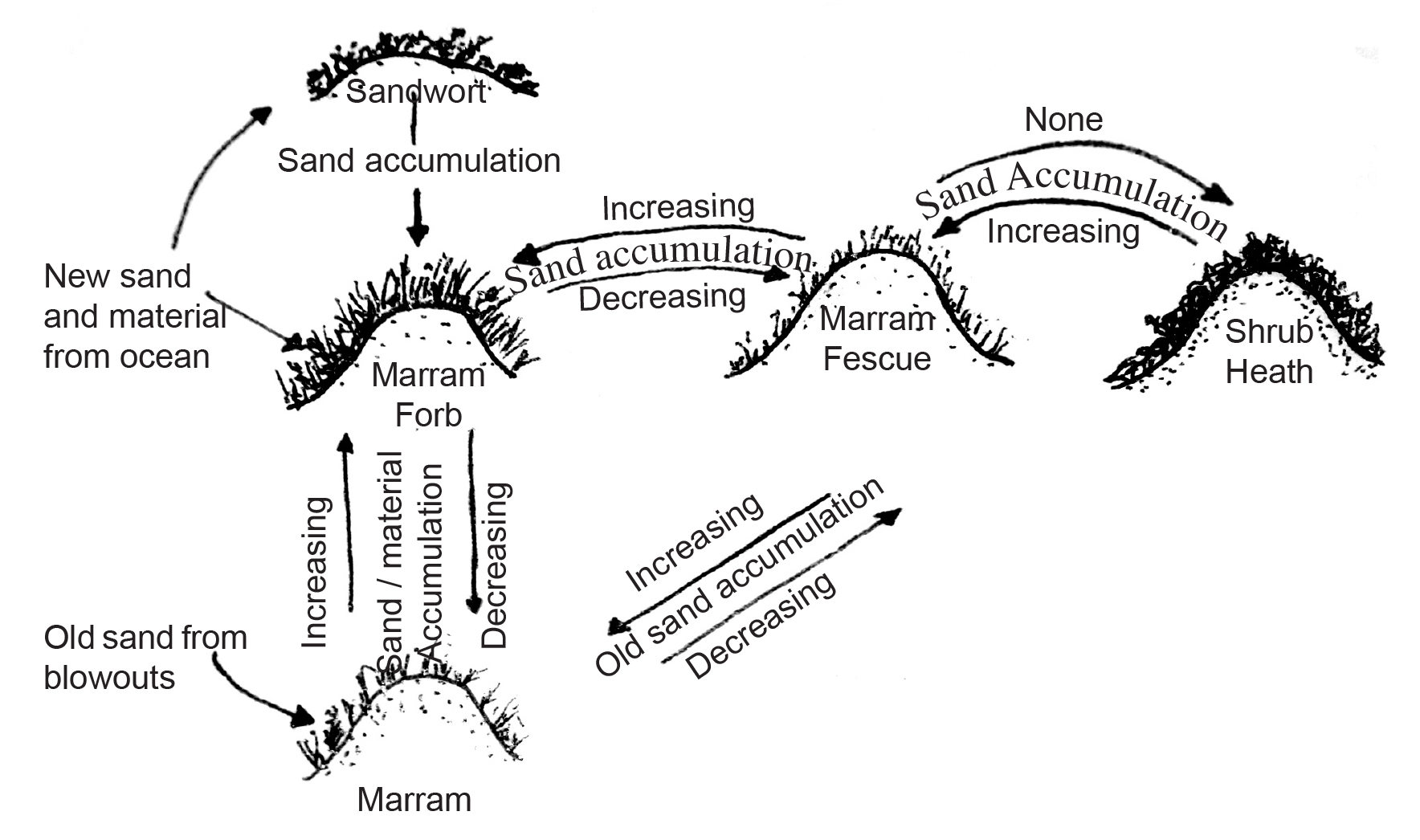

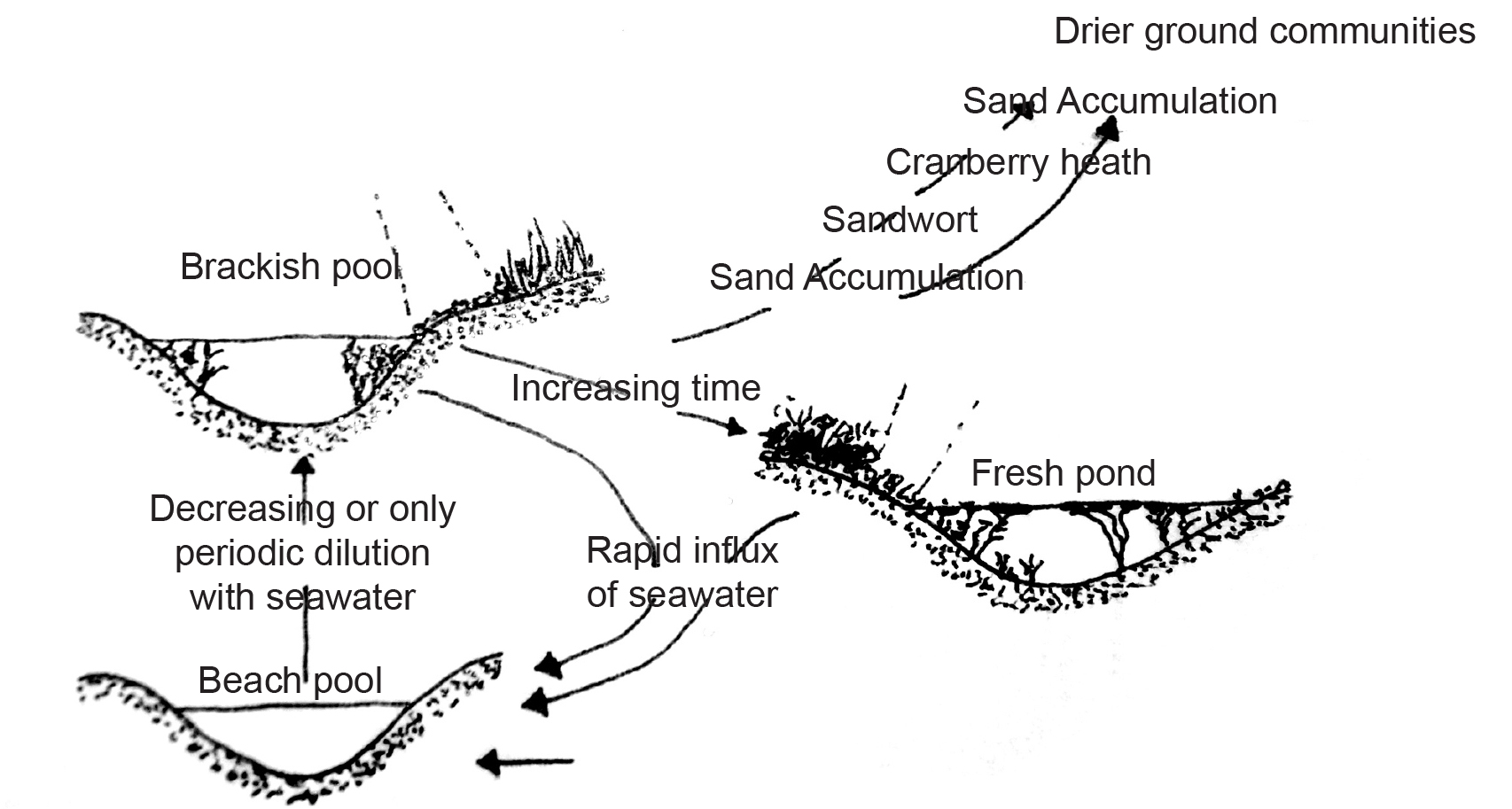

CYCLICAL HABITATS

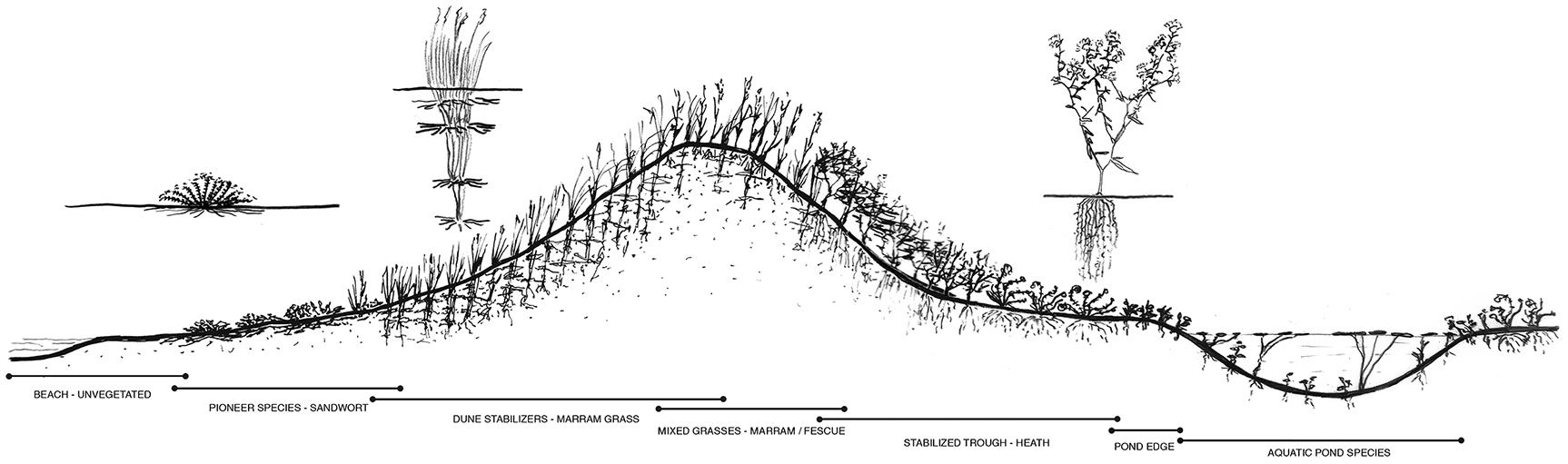

Sable Island’s ecosystem is a cycle of cause and effect scenarios where destruction and creation happen simultaneously. Wind and waves move and sculpt sand while vegetation works to build it into stable mounds and dunes.

Diagrams of sand, water, and vegetation relationships on Sable Island redrawn fromThe Vegetation and Phytogeography of Sable Island, Nova Scotia. Catling, Freedman and Lucas 1984.

VEGETATION

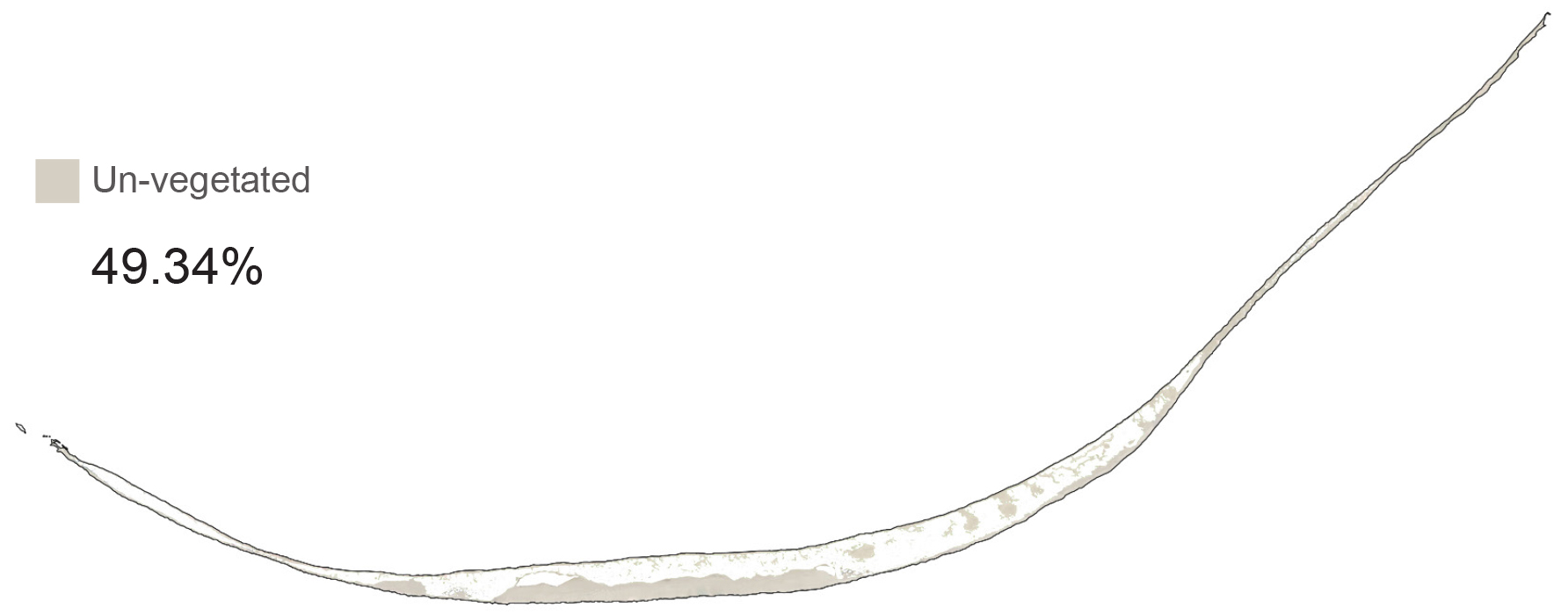

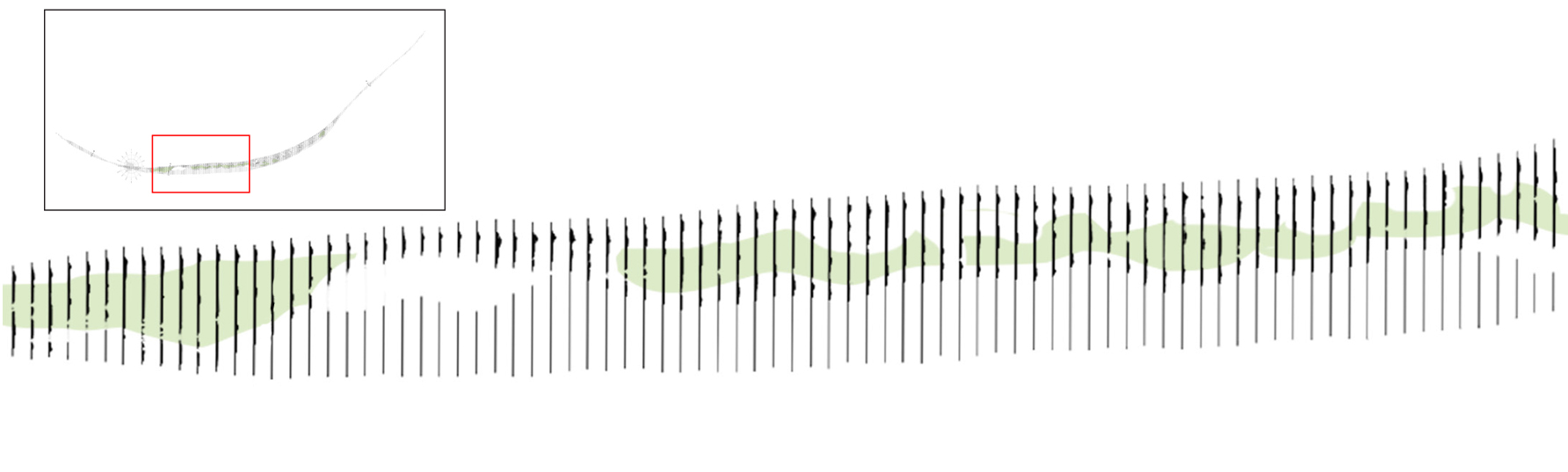

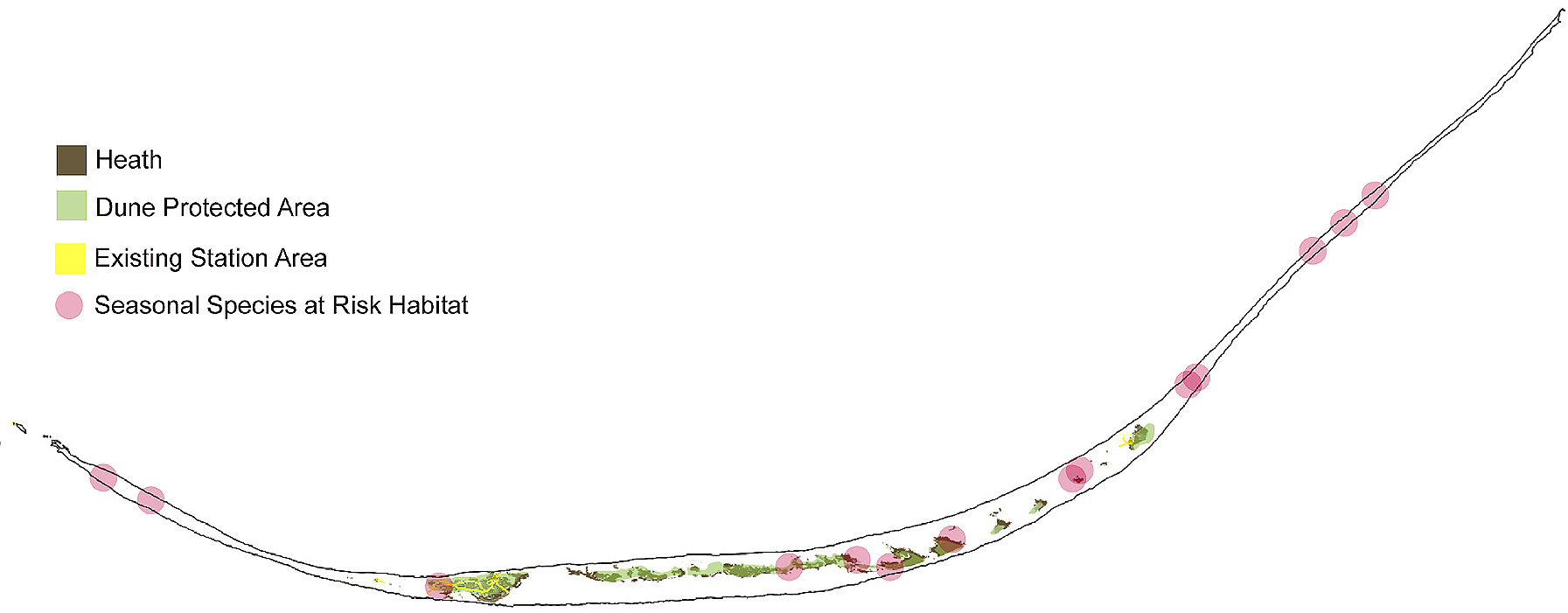

Data gathered from Allison Muise's Sable Island, Nova Scotia: 2009 Topography and Land Cover Atlas can be used to develop design guidelines and locate sites for development.

Nearly half of the island is un-vegetated sand: beaches, bald dunes and roads. These areas are very tolerant for human use, but change constantly with wind, tide and currents. Due to their transient nature un-vegetated areas are not suitable for building infrastructure, but are ideal for runways, roads and paths.

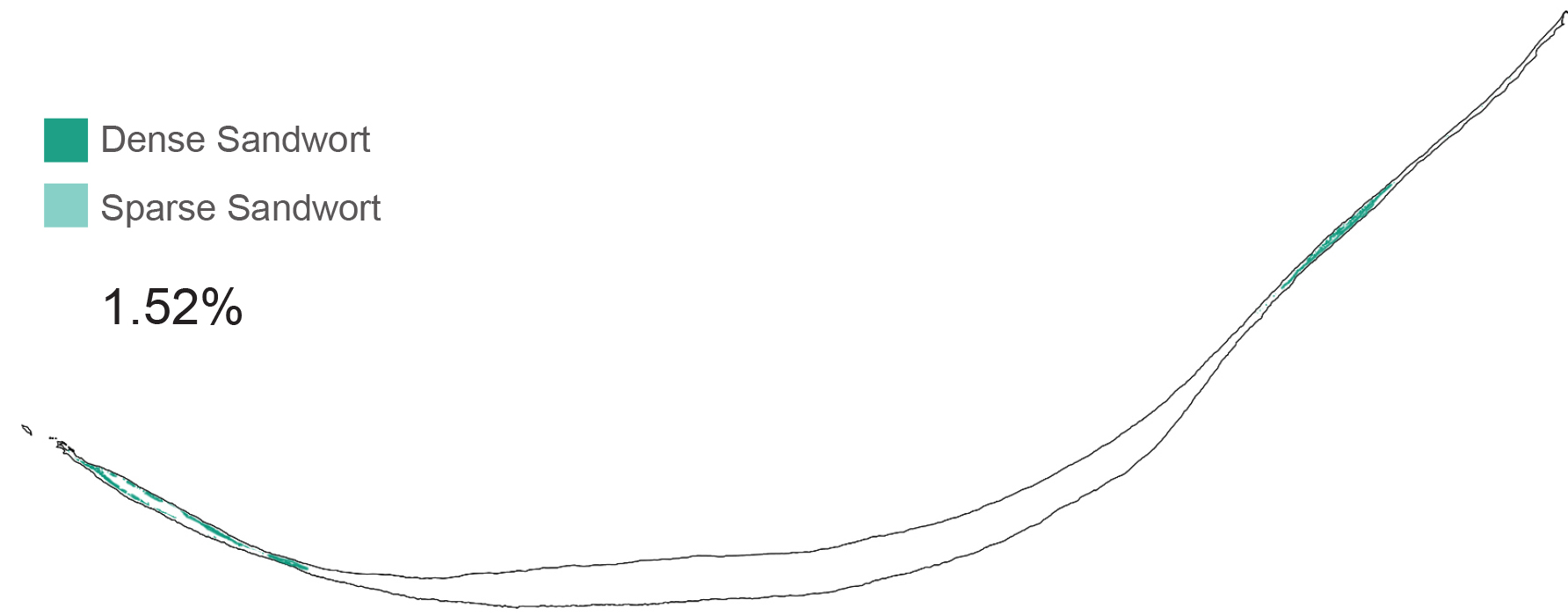

Sandwort is a pioneer plant that inhabits dry conditions on beaches. It tolerates limited salt water flooding and stabilizes sand with its shallow root mesh. The plant collects windblown sand into mounds up to 1 metre high; providing dry habitat for marram grass to grow. Sandwort habitat is not recommended for infrastructure development because it populates changing edges that are often flooded by the ocean.

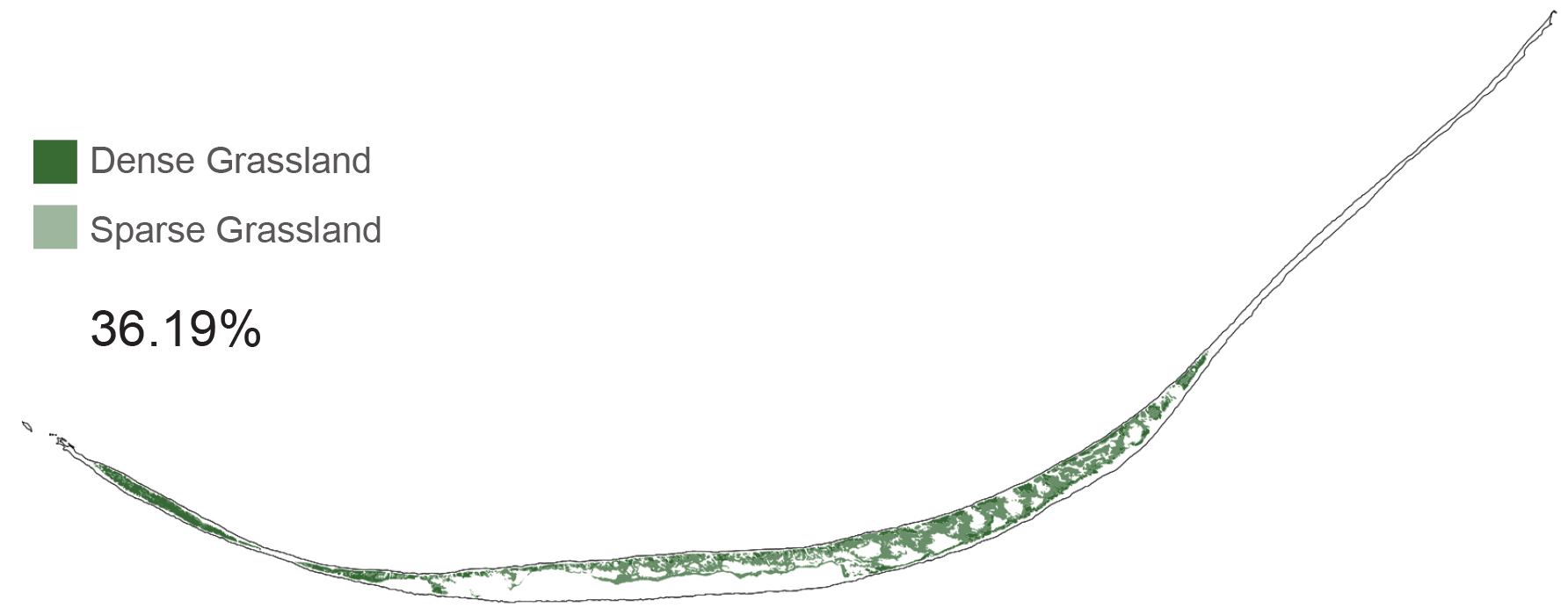

Marram grasses have deep, dune stabilizing root structures; growing in dry areas, their blades catch wind-blown sand to form dunes. It grows through accumulating sand forming annual stabilizing root mats. Marram grass is easily killed when trampled, leading to aggressive dune erosion. Human activity should not occur in dune habitats to avoid damaging protective dune systems.

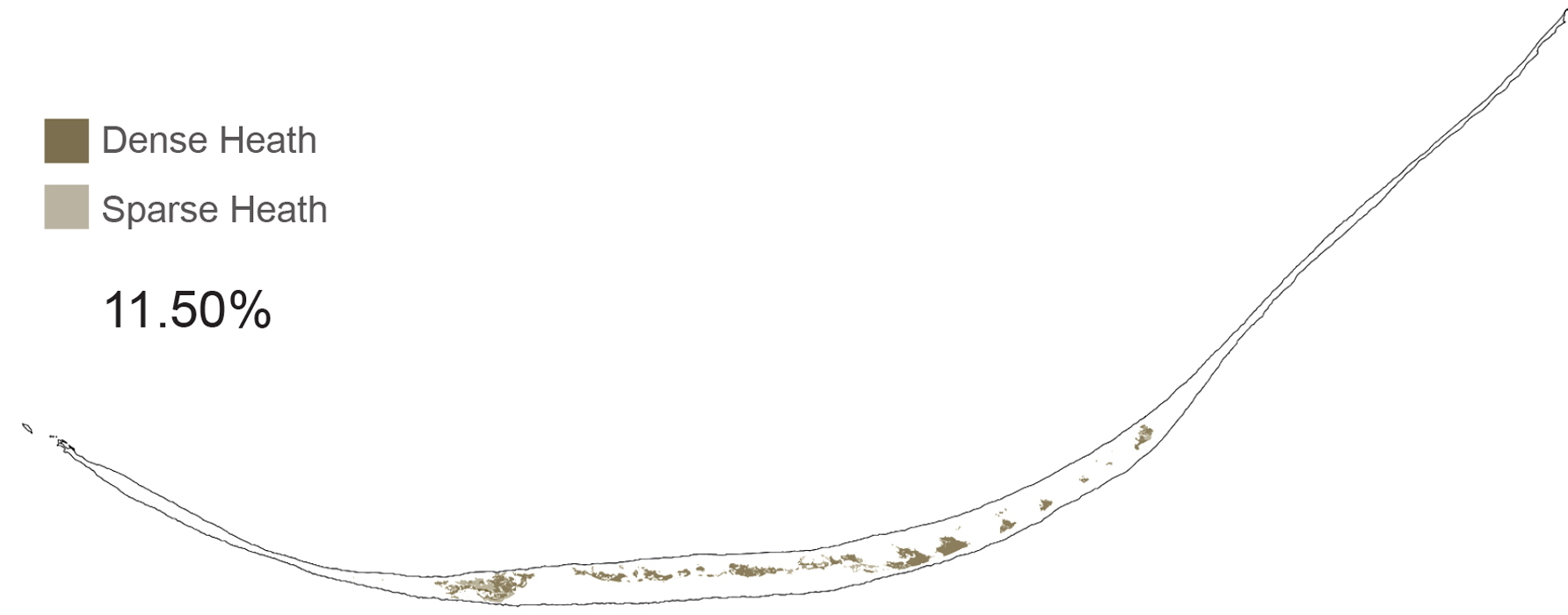

Heath grows in weather protected environments between well established dune systems and often near fresh water ponds. Its habitat occurs in well stratified landscapes that have grown for a long time without significant change. Their dense roots are strong and tolerant to trampling; heath habitats are ideal for human habitation.

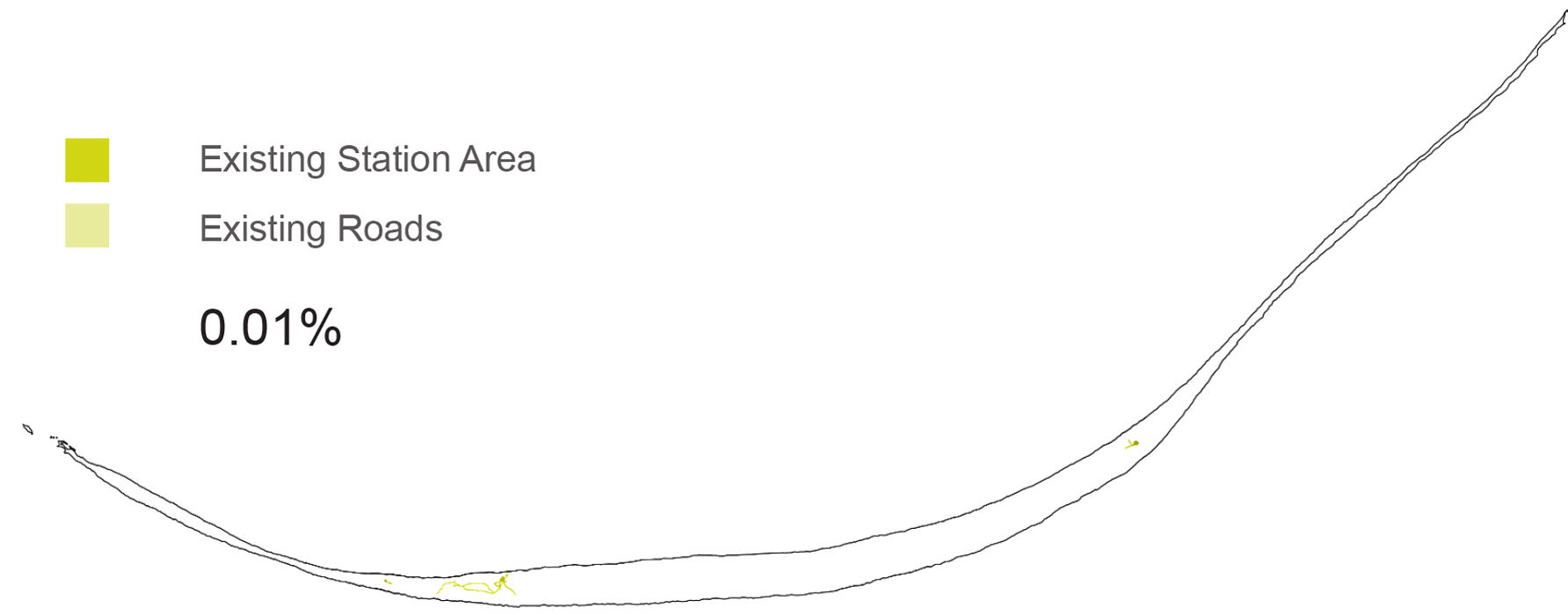

Reusing existing station areas reduces environmental impact because they are already connected to the beaches by sand roads and disruption of undeveloped habitat would not be required.

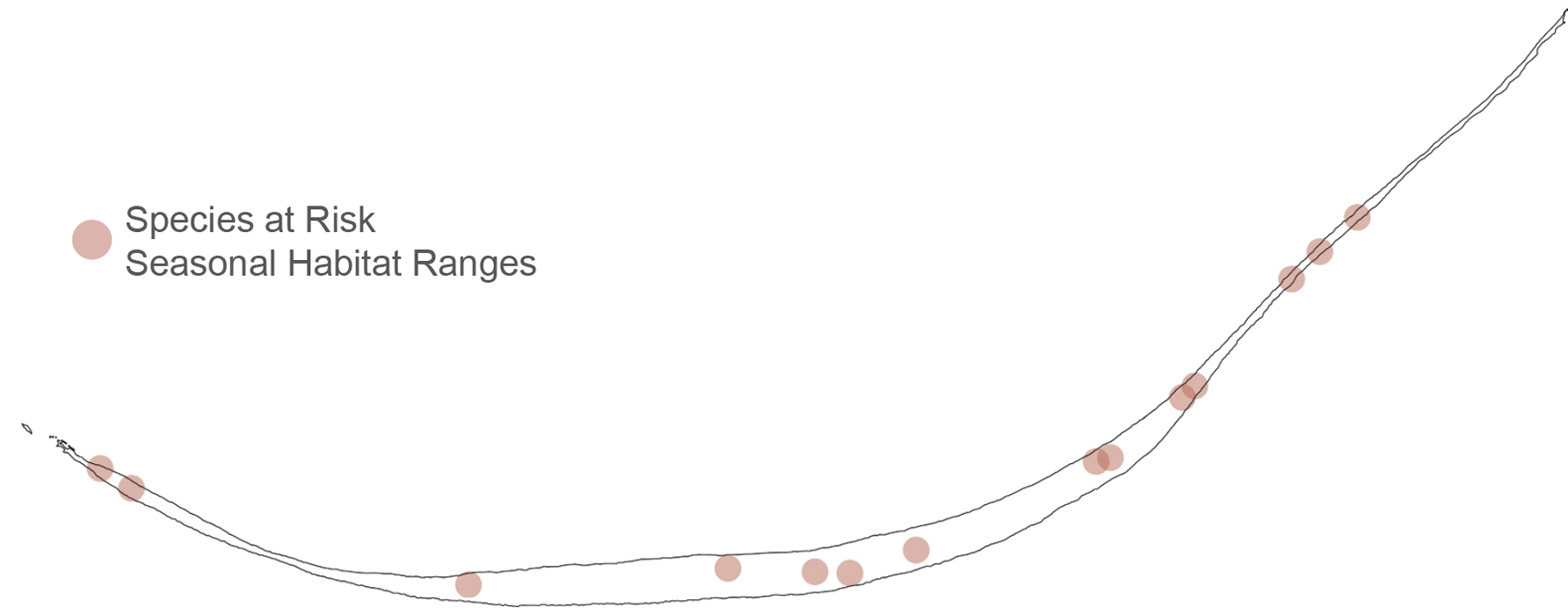

Major development should be avoided in seasonal species at risk breeding habitats, but research and seasonal use shelters near these areas can be useful.

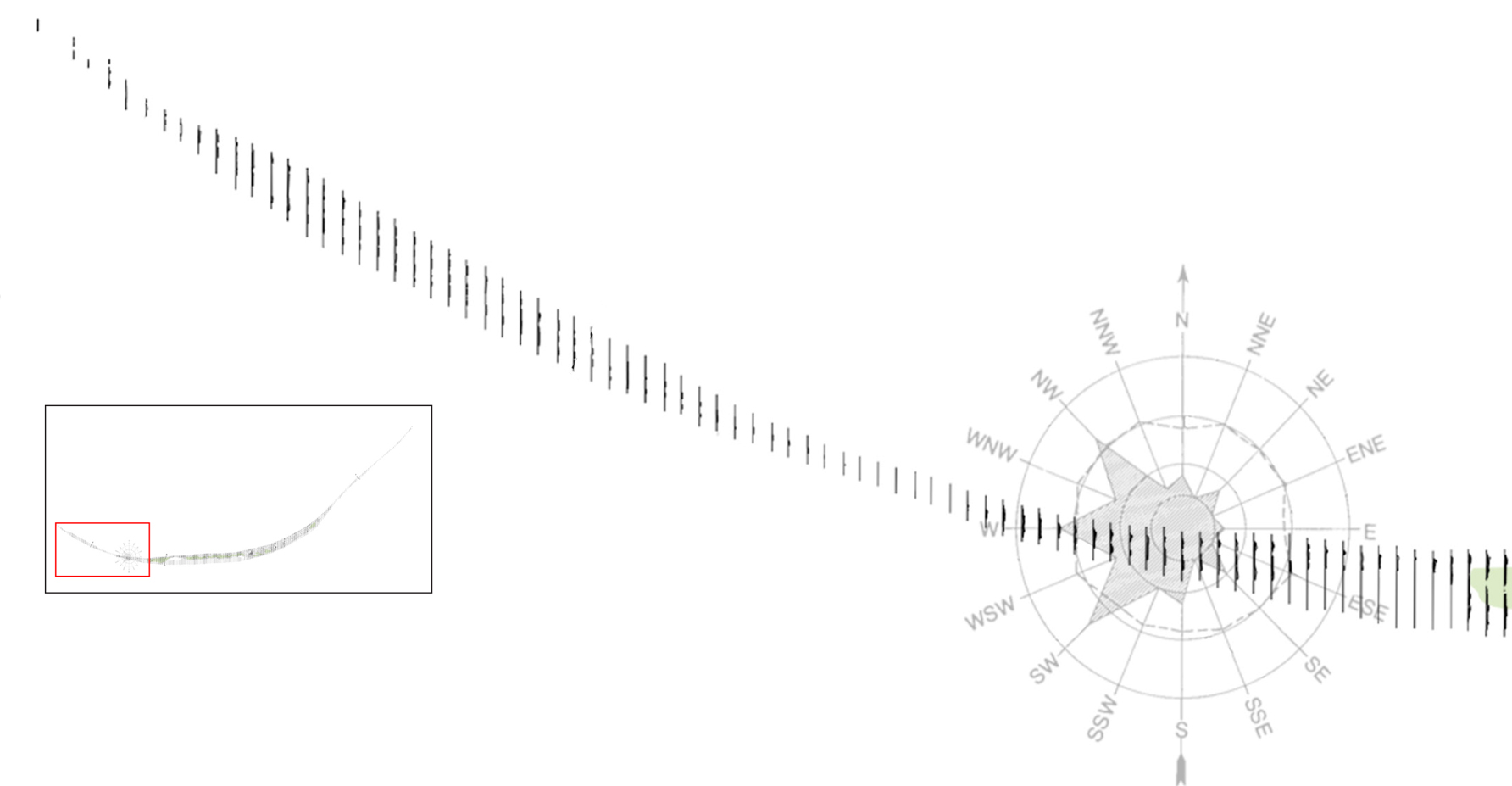

TOPOGRAPHY

Analysis of topography helps identify dune protected habitats suitable for human habitation.

The West Spit, historically the most changed part of the island, is very low and exposed. It is the first landfall point for storms and winds. Very little protected dune habitat exists here. If development occurs here it should be easy to relocate in case of major landscape change.

The centre of the island is historically the most stable part of the island. It has strong constant dune systems. Dunes formed on an east-west axis break prevailing wind speeds. North and South dunes protect the inland trough from storm winds. This widest dune protected habitat is the most tolerant site on the island; the landscape here is slow to change and suitable for development.

The trough overlooking the wide South beach is also well protected, but is so narrow that potential dune blow outs and wash outs could undermine developments. Any infrastructure there would require a resettlement plan.

As the island turns North the prevailing winds make landfall with full strength, moving sand and creating a turbulent terrain. Bald Dune, a massive accumulation of windblown sand is the highest point on the island and an important tourism site as it provides excellent views of the island.

Some areas in this section of the island are protected by dune systems, but could easily be breached during strong winds. Any development in these areas should be easy to relocate in the event of major terrain changes.

East Spit is very low and exposed. It is one of the most frequently changed habitats. Very exposed to high winds and wash over from storms, the landscape is not fit for development.

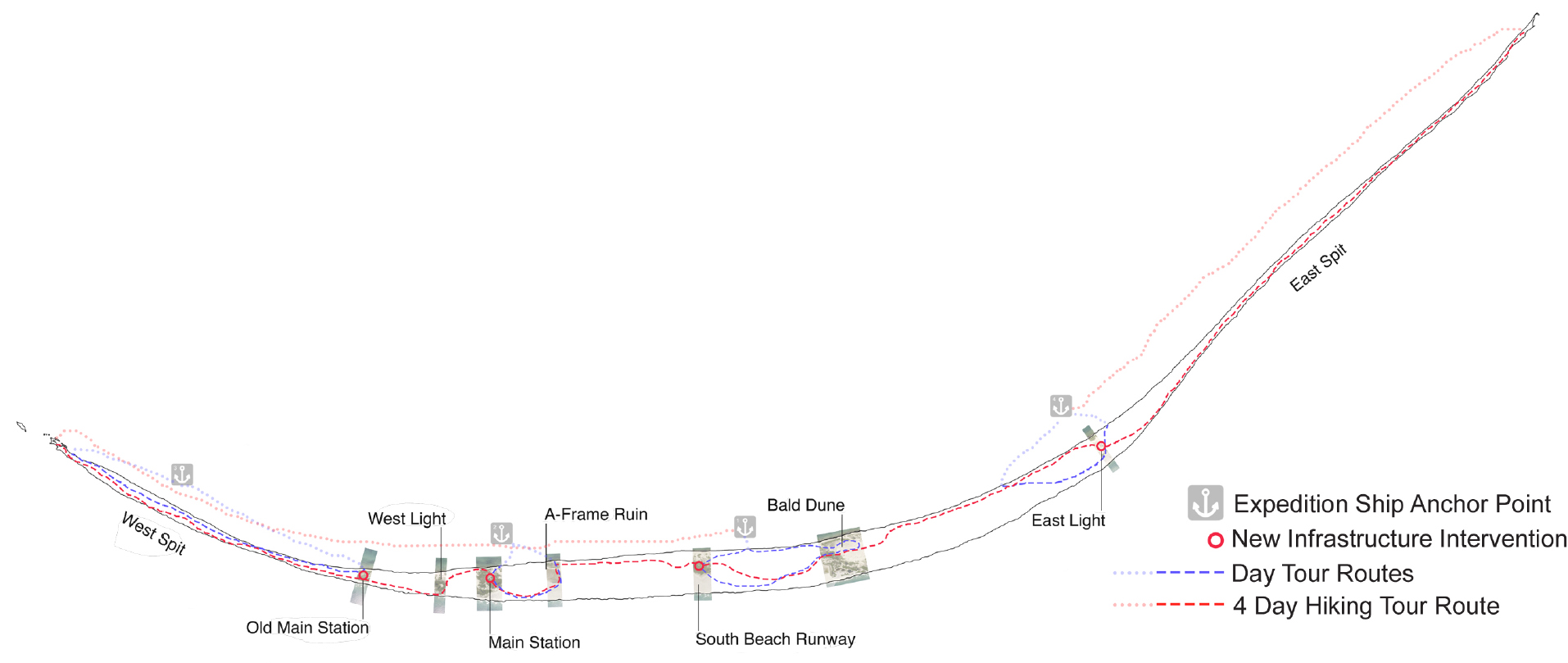

SITE SELECTION

Island and ecosystem analyses have provided a set of guidelines for infrastructure development. By overlaying the collected data on one map, it is possible to identify ideal sites for development.

Site and ecosystem analyses provide guidelines for determining where to build National Park infrastructure on Sable Island: vegetation analyses show that heath habitat is strong and tolerant to human use and topography analyses identify dune protected environments. The parts of the island where these attributes overlap with beneficial existing infrastructure, and avoid species at risk habitat, are ideal for development. A network of four architectural interventions built in these sites will provide safe refuge for emergencies across the island and provide all necessary National Park amenities.

The proposed island plan links access points, sites of interest and new infrastructure. The network of buildings and hiking paths facilitates exploration of the island for researchers and tourists. The four structures occupy very different landscape dynamics and require site specific design strategies.